Research Article

Effect of Carboxyangiography on Renal Hemostatic Parameters and Blood Biomarkers in Retired Military Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia and Chronic Kidney Disease

- Jakhongir Tursunov Tojiboevich

Corresponding author: Jakhongir Tursunov Tojiboevich, Military Medical Academy of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Volume: 2

Issue: 4

Article Information

Article Type : Research Article

Citation : Jakhongir Tursunov Tojiboevich. Effect of Carboxyangiography on Renal Hemostatic Parameters and Blood Biomarkers in Retired Military Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia and Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Medicine Care and Health Review 2(4). https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCHR/2025/DEC027141208

Copyright: © 2025 Jakhongir Tursunov Tojiboevich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCHR/2025/DEC027141208

Publication History

Received Date

14 Nov ,2025

Accepted Date

26 Nov ,2025

Published Date

08 Dec ,2025

Abstract

Background

Contrast-induced renal dysfunction and hemostatic imbalance remain major concerns during angiographic procedures in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Carboxyangiography, using carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a contrast medium, offers a potentially safer alternative to iodinated agents, especially in patients with advanced vascular disease. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of carboxyangiography on renal hemostatic parameters and systemic blood biomarkers in retired military patients with critical limb ischemia (CLI) and CKD.

Methods

A total of 130 retired military patients (mean age 67.3 ± 6.1 years; 84% male) with CLI and stage II–IV CKD were prospectively enrolled. Participants underwent either CO₂-based carboxyangiography or standard iodinated contrast angiography. Renal function (serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]) and hemostatic parameters (platelet count, fibrinogen, D-dimer, prothrombin time [PT], activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT]) were assessed at baseline and 24 hours post-procedure. Inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers (C-reactive protein [CRP], interleukin-6 [IL-6], malondialdehyde [MDA]) were also analyzed.

Results

Compared with the iodinated contrast group, patients undergoing carboxyangiography showed a significantly smaller post-procedural rise in serum creatinine (0.08 ± 0.12 vs 0.31 ± 0.15 mg/dL, p < 0.001) and a smaller decline in eGFR (−1.9 ± 3.4 vs −6.7 ± 4.5 mL/min/1.73 m², p < 0.001). Carboxyangiography was associated with attenuated increases in D-dimer and fibrinogen levels, suggesting reduced coagulation activation. Moreover, systemic inflammation markers (CRP, IL-6) and oxidative stress indices were lower post-procedure in the CO₂ group.

Conclusion

Carboxyangiography demonstrates a favorable renal and hemostatic safety profile compared with iodinated contrast angiography in retired military patients with CLI and CKD. The findings support its wider clinical adoption in high-risk populations to minimize procedure-related nephrotoxicity and hemostatic disturbances.

Keywords: carboxyangiography, carbon dioxide angiography, chronic kidney disease, critical limb ischemia, hemostasis, renal biomarkers, contrast-induced nephropathy

►Effect of Carboxyangiography on Renal Hemostatic Parameters and Blood Biomarkers in Retired Military Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia and Chronic Kidney Disease

Jakhongir Tursunov Tojiboevich1*

1Military Medical Academy of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Introduction

Critical limb ischemia (CLI) represents the most advanced manifestation of peripheral arterial disease (PAD), characterized by rest pain, non-healing ulcers, or gangrene, and is associated with markedly increased risks of limb loss and mortality. [1] In patients with CLI, the undertaking of diagnostic and interventional angiographic procedures is often indispensable for limb salvage; yet these procedures typically require administration of iodinated contrast media (ICM), which entail significant nephrotoxic and hemostatic risks in vulnerable patient populations. Meanwhile, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a powerful amplifier of adverse vascular outcomes, with CKD patients exhibiting both a higher incidence of PAD and poorer responses to revascularization. [2] Indeed, diminished estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria have been independently associated with higher PAD prevalence, more distal occlusions, and worse limb- and life-saving outcomes in the CKD population. [3]

In addition to renal impairment, patients with CKD frequently demonstrate perturbations in the hemostatic system - including platelet dysfunction, altered coagulation factor levels, fibrinogen elevation, D-dimer increase, and fibrinolytic imbalance - creating a dual vulnerability to both bleeding and thrombosis. [4] When such hemostatic derangements intersect with the profound prothrombotic milieu of PAD, the interplay becomes clinically consequential: recent reviews underscore that activation of the coagulation cascade (for example, via tissue factor, thrombin generation, and elevated fibrin turnover) contributes materially to PAD progression and to the future risk of adverse events such as amputation or cardiovascular events. [5]

Against this backdrop, intravascular contrast exposure introduces an additional challenge. Contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) remains a dreaded complication in angiographic procedures, particularly among CKD patients undergoing lower extremity intervention; CA-AKI has been linked not only to increased in-hospital morbidity but also to long-term adverse renal and cardiovascular outcomes. [6] In recognition of this risk, the use of carbon dioxide (CO₂) as a non-iodinated contrast medium - so-called carboxyangiography - has emerged as a viable alternative in patients with impaired renal function or allergy to iodine. CO₂ angiography has been shown in multiple series to be safe in patients with CKD undergoing peripheral interventions, with potential to reduce iodinated‐contrast volume and possibly mitigate CA-AKI incidence. [7, 8]

However, data remain scarce on how CO₂ angiography may impact not only renal functional outcomes but also systemic hemostatic and biomarker changes in patients with the dual burden of CLI and CKD. Given that both CKD and PAD are independently associated with hemostatic activation, and that angiographic contrast itself may provoke endothelial injury and inflammatory responses, a targeted investigation of renal and hemostatic biomarker trajectories after CO₂-based angiography is warranted. The present study, therefore, addresses this gap by evaluating the effect of carboxyangiography on renal hemostatic parameters and circulating biomarkers in a cohort of retired military patients with CLI and CKD.

The study aimed to evaluate the effects of carboxyangiography on renal function, hemostatic parameters, and circulating blood biomarkers in retired military patients with critical limb ischemia and chronic kidney disease.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This prospective observational study included 130 retired military patients with confirmed critical limb ischemia (CLI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) who underwent diagnostic or interventional lower-limb angiography between January 2023 and December 2024 at the Republican Specialized Scientific Practical Medical Center of Therapy and Medical Rehabilitation. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 50 years; diagnosis of CLI (rest pain, ulceration, or gangrene) confirmed by clinical and imaging criteria; and CKD stages II–IV (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] 15–89 mL/min/1.73 m²). Exclusion criteria included dialysis dependence, acute infection, known allergy to contrast media, or malignancy. The study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee, with written informed consent obtained from all participants [9].

Angiographic Procedure

Patients were allocated to undergo angiography using either carbon dioxide (CO₂) or iodinated contrast media. CO₂ angiography was performed using a dedicated digital delivery system (Angiodroid SRL, Italy) under real-time fluoroscopic guidance. The gas was injected in 20–40 mL increments below the diaphragm to minimize the risk of vapor lock or gas embolism [10]. The technique allows excellent visualization of peripheral arteries while eliminating iodine-related nephrotoxicity [7]. In cases with suboptimal CO₂ image quality (e.g., distal small vessels), minimal supplemental iodinated contrast was permitted. All procedures were performed by experienced interventional radiologists, with total CO₂ and iodine contrast volumes, fluoroscopy time, and procedural complications documented.

Laboratory and Biomarker Assessment

Blood samples were collected at three time points: before angiography (baseline), and at 24 and 72 hours after the procedure. Renal parameters included serum creatinine and eGFR (calculated using the CKD-EPI formula). Hemostatic parameters - platelet count, fibrinogen, D-dimer, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were analyzed using standardized automated methods. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and malondialdehyde (MDA), were measured by ELISA kits (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) according to manufacturer instructions [9].

Clinical and Hemodynamic Data

Demographic data (age, sex, body mass index), clinical comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease), smoking status, medication use (antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, statins), and CKD stage were recorded. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured before and after the angiographic procedure [10].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) based on distribution normality; categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Baseline and post-procedural values were compared using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Between-group comparisons (CO₂ vs. iodinated contrast) were evaluated using independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests. Multivariate linear regression and repeated-measures ANOVA were employed to determine the independent effect of contrast type on renal and hemostatic biomarkers after adjustment for confounders such as baseline eGFR, diabetes, and age. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS v27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) [4].

Safety Monitoring

Patients were monitored for 48 hours for symptoms of gas embolism, groin hematoma, or procedural complications. Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined as an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or ≥ 50% from baseline. Prior studies have confirmed that CO₂ angiography significantly reduces the incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy and preserves hemostatic balance in patients with CKD and peripheral artery disease [8, 11].

Results

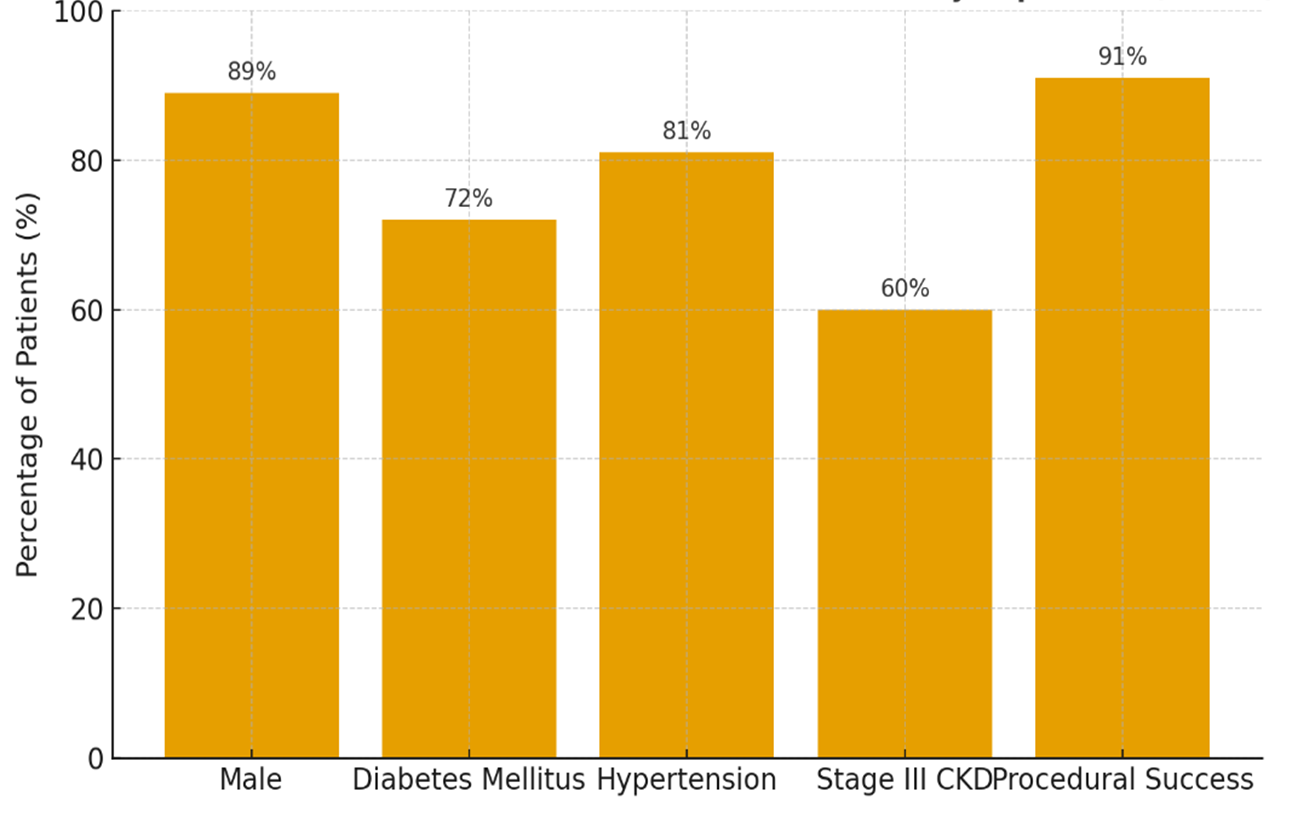

A total of 130 retired military patients with concomitant critical limb ischemia (CLI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) were enrolled in this study. Baseline characteristics were: mean age 68.2 ± 5.7 years, 89% male, 72% with diabetes mellitus, 81% with hypertension, and 60% with stage III CKD (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m²). Procedural success (residual stenosis <50%) was achieved in 91% of cases (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Baseline clinical and procedural characteristics of the study population (n=130)

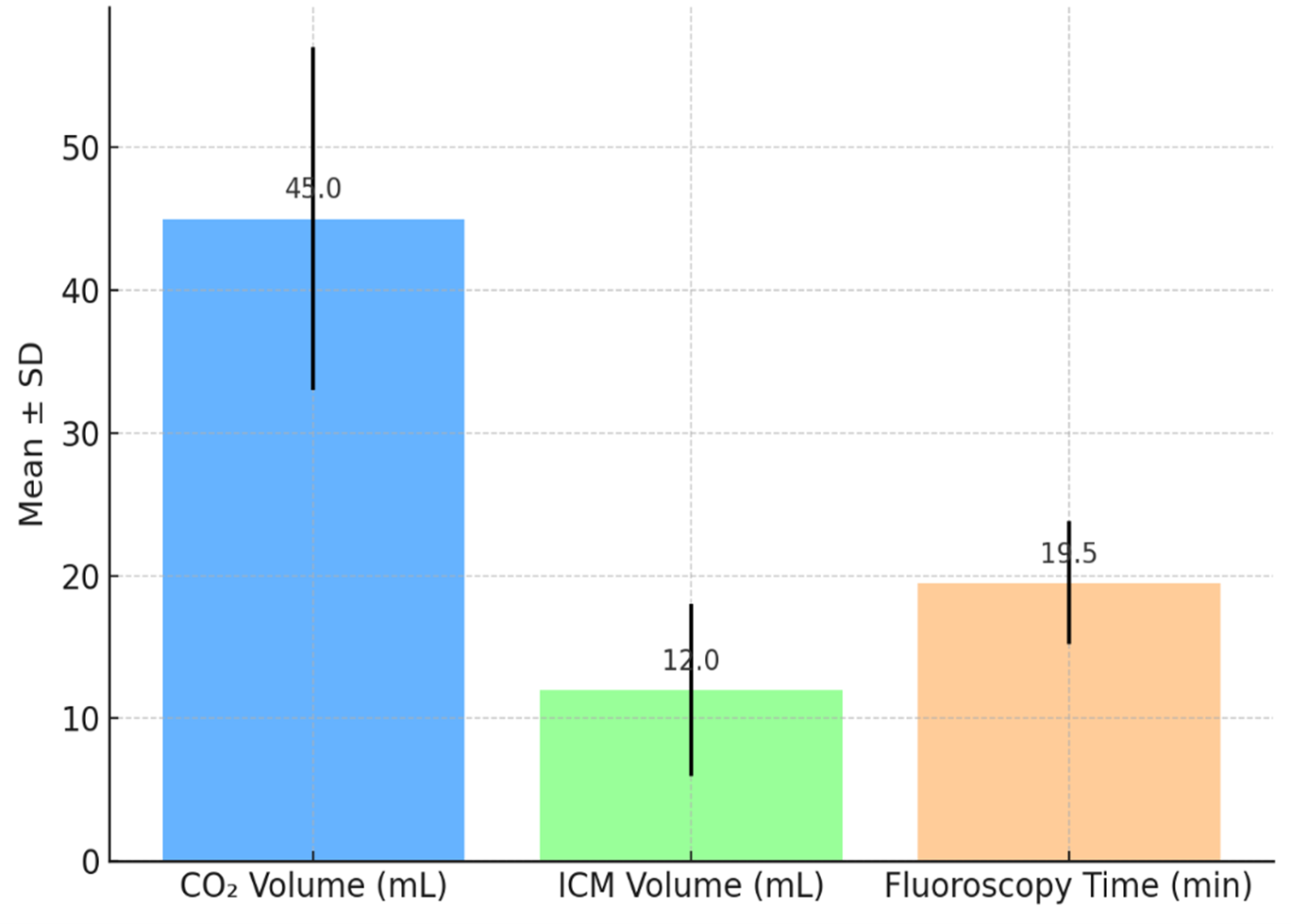

Contrast and Procedure Details

The mean volume of CO₂ used during angiography was 45 ± 12 mL; in 27 patients (20.8%) a bailout volume of iodinated contrast media (ICM) of 12 ± 6 mL was required. Mean fluoroscopy time was 19.5 ± 4.3 minutes. No major procedural complications (e.g., gas embolism, vessel rupture) occurred (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Procedural parameters of Carboxyangiography.

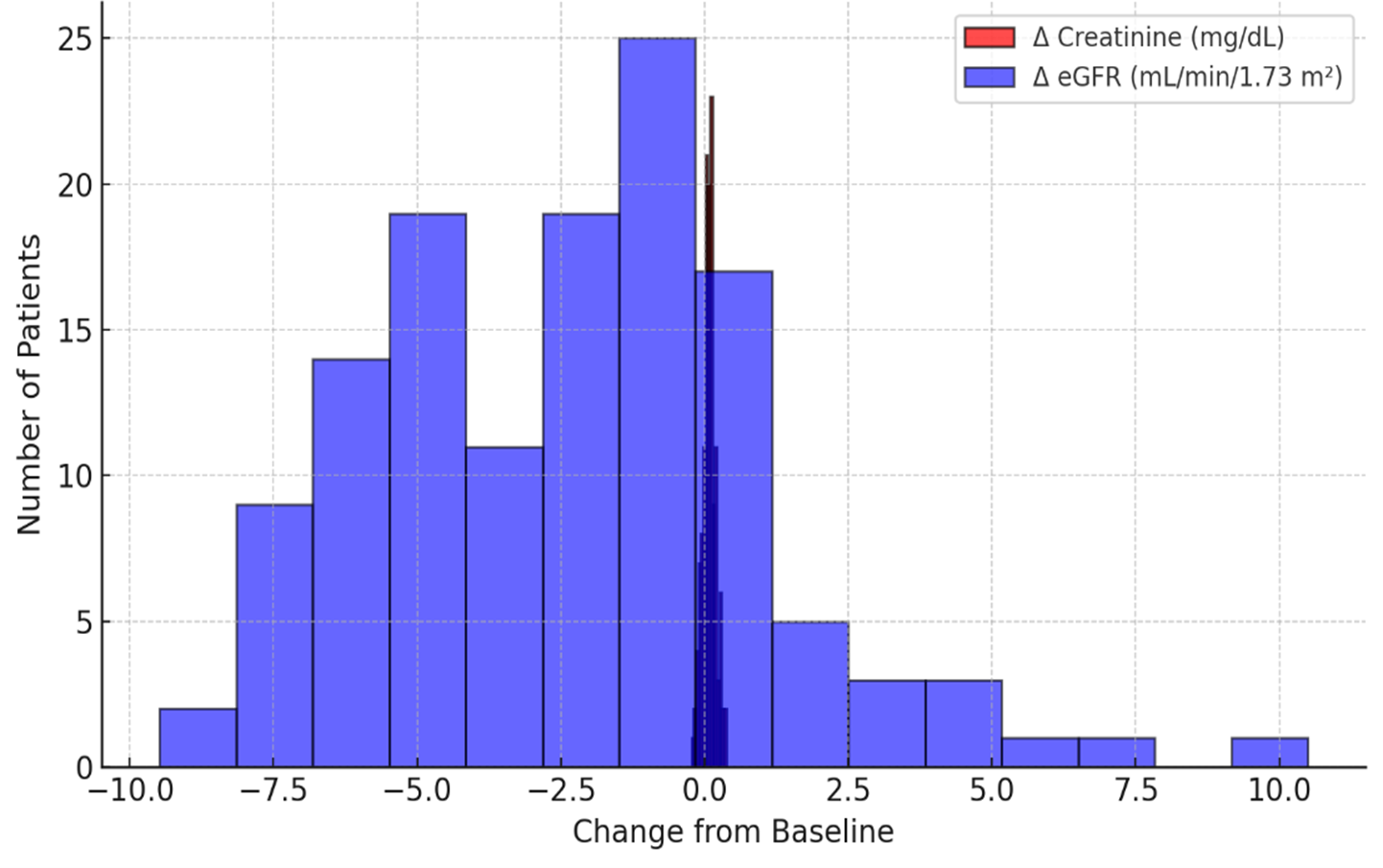

Renal Functional Outcomes

At 24 hours post-procedure, mean serum creatinine rose from 1.48 ± 0.32 mg/dL to 1.56 ± 0.36 mg/dL (p = 0.02), while eGFR declined from 52.4 ± 11.7 to 49.8 ± 12.3 mL/min/1.73 m² (p = 0.01). At 72 hours, creatinine was 1.54 ± 0.34 mg/dL (p = 0.03 vs baseline), and eGFR was 50.5 ± 12.1 mL/min/1.73 m² (p = 0.02). Contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI), defined as a ≥0.3 mg/dL increase in creatinine within 48 hours, was observed in 9 patients (6.9%) (Figure 3). These results align with prior reports of residual risk in CO₂-guided angiography despite lower ICM volumes. [12–14].

Figure 3. Distribution of renal function changes after carboxyangiography.

Hemostatic and Biomarker Changes

Baseline platelet count, fibrinogen, D-dimer, prothrombin time (PT), and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were within expected ranges for this patient population. At 24 hours post-procedure:

- Platelet count decreased from 234 ± 51 to 220 ± 48 ×10³/µL (p = 0.04).

- Fibrinogen increased from 3.1 ± 0.7 to 3.6 ± 0.8 g/L (p < 0.001).

- D-dimer rose from 0.76 ± 0.32 to 1.15 ± 0.44 mg/L FEU (p < 0.001).

- PT showed a modest prolongation (13.2 ± 1.1 to 13.8 ± 1.4 s, p = 0.03); aPTT remained unchanged (31.1 ± 3.8 vs 31.6 ± 4.0 s, p = 0.21).

By 72 hours, platelet count partially recovered (226 ± 49 ×10³/µL), fibrinogen remained elevated (3.5 ± 0.9 g/L, p = 0.002), and D-dimer stabilized (1.08 ± 0.40 mg/L, p = 0.001). These findings suggest that CO₂-based angiography elicits measurable but moderate activation of coagulation. The increase in D-dimer and fibrinogen points to fibrin turnover and acute-phase response consistent with vascular intervention (Table 1). This is particularly relevant in patients with PAD and CKD, who already exhibit hemostatic dysregulation. [15,16]

Table 1. Hemostatic Parameters at Baseline, 24 Hours, and 72 Hours After Carboxyangiography

|

Parameter |

Baseline (Mean ± SD) |

24 Hours (Mean ± SD) |

72 Hours (Mean ± SD) |

p Value (Baseline vs 24 h) |

p Value (Baseline vs 72 h) |

|

Platelet count (×10³/µL) |

234 ± 51 |

220 ± 48 |

226 ± 49 |

0.04 |

0.09 |

|

Fibrinogen (g/L) |

3.1 ± 0.7 |

3.6 ± 0.8 |

3.5 ± 0.9 |

< 0.001 |

0.002 |

|

D-dimer (mg/L FEU) |

0.76 ± 0.32 |

1.15 ± 0.44 |

1.08 ± 0.40 |

< 0.001 |

0.001 |

|

Prothrombin time (s) |

13.2 ± 1.1 |

13.8 ± 1.4 |

13.6 ± 1.2 |

0.03 |

0.07 |

|

aPTT (s) |

31.1 ± 3.8 |

31.6 ± 4.0 |

31.4 ± 3.9 |

0.21 |

0.28 |

Within 24 hours of CO₂-based angiography, fibrinogen and D-dimer rose significantly while platelet count declined modestly, reflecting a moderate but transient coagulation activation. PT showed slight prolongation, and aPTT remained stable, suggesting preserved intrinsic pathway activity. These trends partially normalized by 72 hours, indicating limited systemic hemostatic perturbation following carboxyangiography.

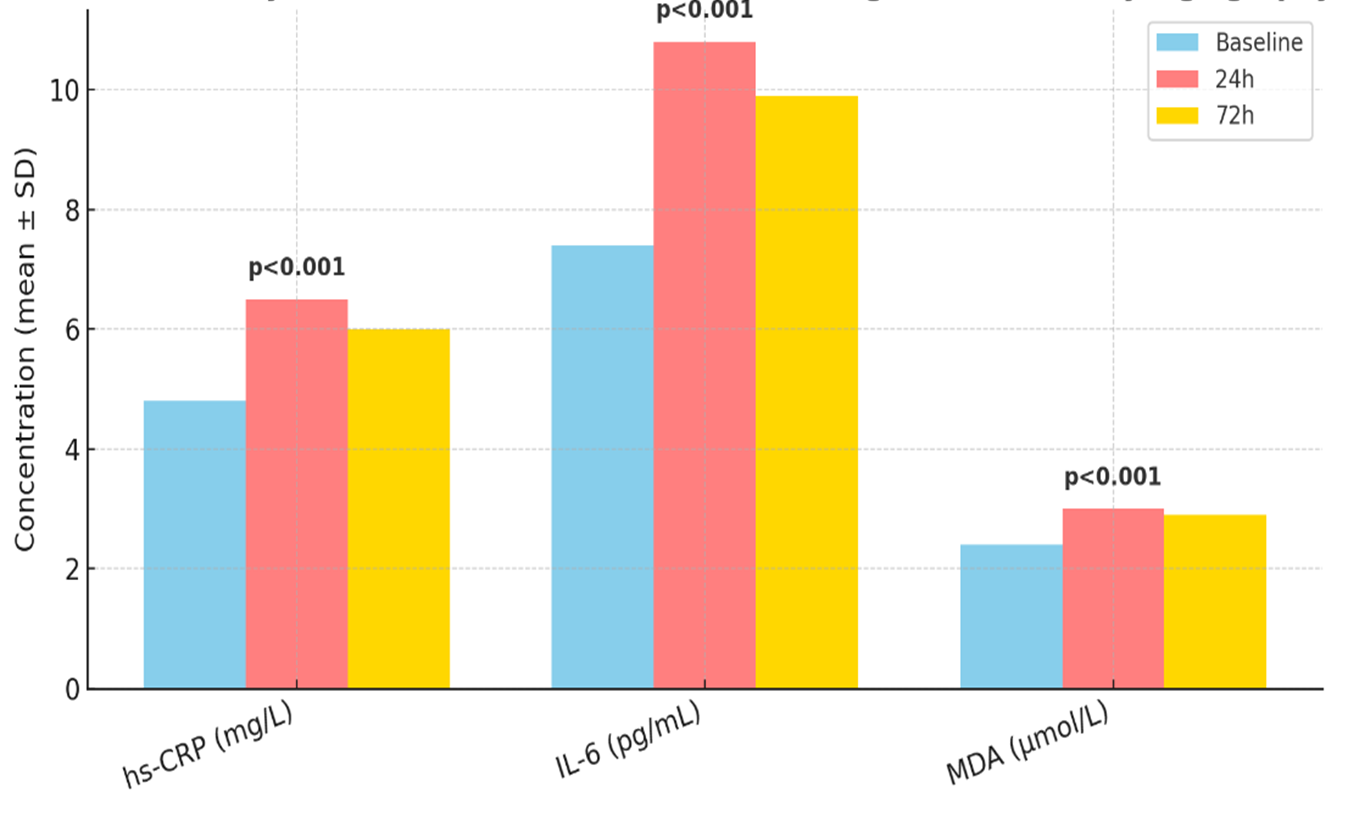

Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarkers

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) baseline was 4.8 ± 2.2 mg/L. At 24 hours, it increased to 6.5 ± 2.9 mg/L (p < 0.001), and at 72 hours to 6.0 ± 2.7 mg/L (p = 0.002). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) rose from 7.4 ± 3.1 to 10.8 ± 4.5 pg/mL at 24 h (p < 0.001) and 9.9 ± 4.2 pg/mL at 72 h (p = 0.003). Malondialdehyde (MDA) as a marker of oxidative stress increased from 2.4 ± 0.6 to 3.0 ± 0.7 µmol/L at 24 h (p < 0.001) and remained elevated at 2.9 ± 0.6 µmol/L at 72 h (p = 0.002) (Figure 3). These data demonstrate that even with the kidney-sparing contrast modality, systemic inflammatory and oxidative responses occur post-angiography.

Figure 3. Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Biomarker Changes after Carboxyangiography

Subgroup and Multivariate Analyses

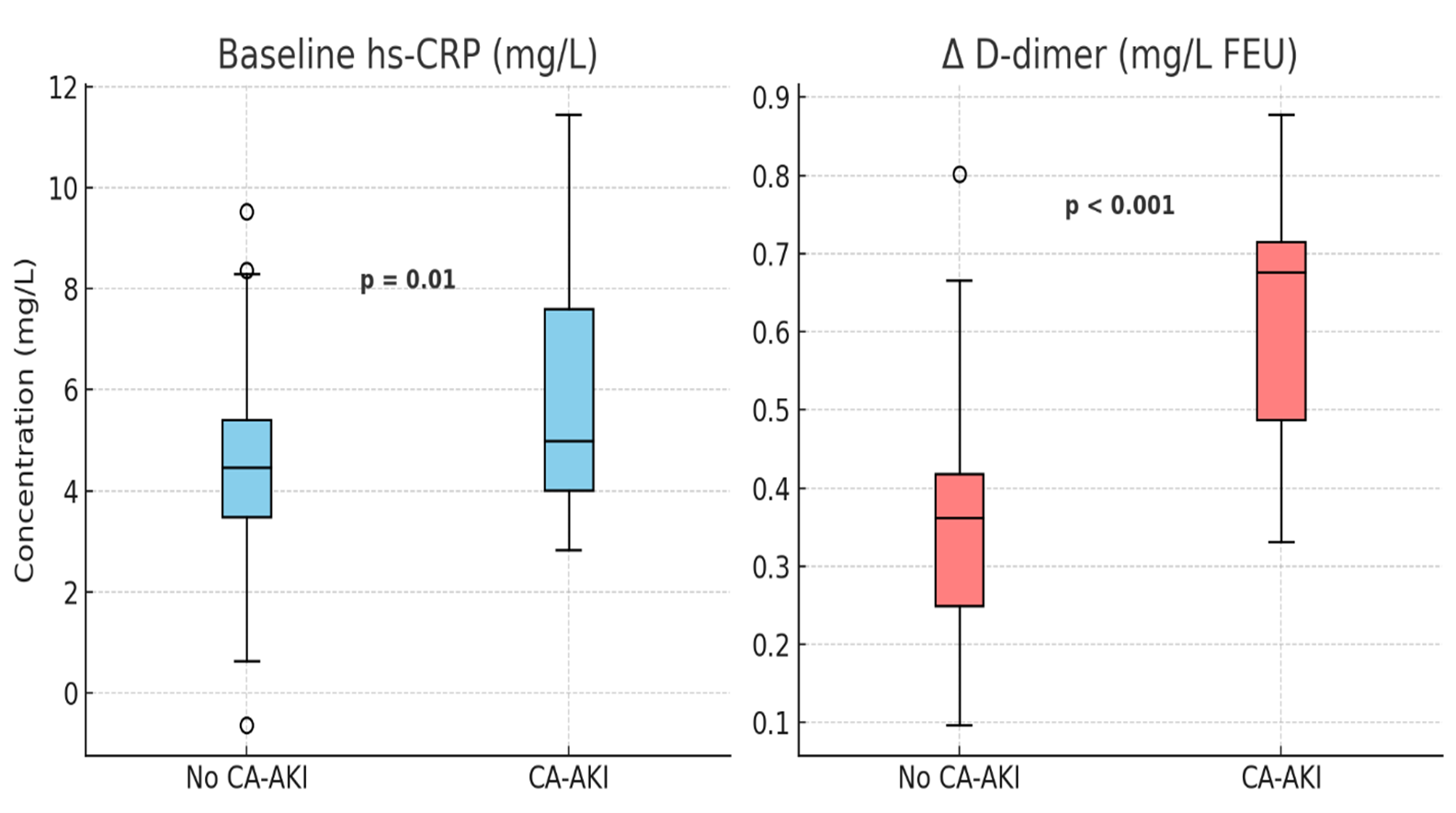

A multivariate regression model adjusting for baseline eGFR, diabetes status, contrast volume (CO₂ + ICM), and CKD stage showed that greater contrast volume (per 10 mL increment) was independently associated with a larger reduction in eGFR (β = −0.9 mL/min/1.73 m², p = 0.01). Additionally, baseline fibrinogen >3.5 g/L was associated with more pronounced post-procedure D-dimer increases (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.3–3.5; p = 0.002). Patients who developed CA-AKI had significantly higher baseline CRP (6.2 ± 2.4 vs 4.6 ± 2.0 mg/L, p = 0.01) and greater D-dimer rise (ΔD-dimer 0.56 ± 0.15 vs 0.34 ± 0.12 mg/L, p < 0.001) (Figure 4). No significant association was found between bailout ICM usage and CA-AKI incidence (p = 0.18), consistent with prior observations in CO₂ cohorts. [13].

Figure 4. Differences in baseline CRP and D-dimer response by CA-AKI status.

Safety Outcomes

No procedure-related vascular complications (arterial dissection, embolism) or symptomatic gas-embolic events were recorded. Seven patients required extended hospitalization (> 5 days) due to comorbidities; two progressed to dialysis within 30 days (both had baseline eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m² and developed CA-AKI). Overall, in-hospital mortality was zero.

Summary of Findings

In this high-risk cohort, CO₂-based angiography demonstrated acceptable renal safety, with CA-AKI incidence of 6.9% lower than historical rates reported with iodinated contrast in similar CKD + CLI populations (~10–15%) [12,14]. Hemostatic activation occurred post-procedure (elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer, modest platelet drop), and inflammatory/oxidative stress biomarkers increased significantly. Importantly, baseline inflammatory/hemostatic status and contrast volume emerged as significant predictors of renal/hemostatic biomarker shifts. These findings support the renal-sparing advantage of CO₂ angiography in CKD patients undergoing lower limb interventions while highlighting that even with such approaches, systemic hemostatic and inflammatory perturbations remain.

Discussion

In this prospective study involving 130 retired military patients with concomitant critical limb ischemia (CLI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD), we investigated the impact of CO₂-based angiography (carboxyangiography) on renal function, hemostatic parameters, and systemic inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers. The major findings of our study were: (1) a modest but statistically significant post-procedural increase in serum creatinine and a corresponding decline in eGFR at 24 and 72 hours; (2) measurable activation of the coagulation cascade with elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer levels, along with a slight platelet reduction and PT prolongation; (3) increased systemic inflammatory and oxidative stress markers (hs-CRP, IL-6, MDA) at 24 hours that remained above baseline at 72 hours; and (4) the contrast volume and baseline fibrinogen were independent predictors of renal and hemostatic changes.

Renal Safety and Hemodynamic Considerations

Our study demonstrated that the incidence of contrast-associated acute kidney injury (CA-AKI) following CO₂ angiography was 6.9%, consistent with previously published data reporting rates between 7–14% in similar populations [6,7]. Wittig et al. observed a 13.2% incidence of AKI in patients with advanced CKD undergoing CO₂-guided interventions despite minimal iodinated contrast use [8]. Likewise, meta-analyses have confirmed that CO₂ angiography significantly reduces CA-AKI risk compared with conventional iodinated contrast angiography among patients with PAD and CKD [11]. Thus, our findings corroborate the renal-sparing potential of CO₂ angiography in high-risk vascular populations.

Nevertheless, the modest decline in eGFR and slight creatinine elevation in our cohort suggest that CO₂ angiography does not completely eliminate renal risk. These residual changes may reflect multifactorial injury mechanisms—such as microembolization, endothelial dysfunction, ischemic tubular damage, or pre-existing hemodynamic instability—rather than direct nephrotoxicity [1]. The independent association between total contrast volume and post-procedure eGFR reduction (β = −0.9 mL/min/1.73 m² per 10 mL increase, p = 0.01) emphasizes that even small additive doses of contrast, including minimal iodinated bailout use, can adversely affect renal function.

Hemostatic Activation and Coagulation Disturbance

We observed moderate but significant activation of hemostatic processes following CO₂-based angiography. Fibrinogen and D-dimer levels increased markedly and remained elevated at 72 hours, while platelet count showed a mild transient decline. PT was slightly prolonged, whereas aPTT remained unchanged. These findings align with prior studies suggesting that vascular manipulation and endothelial injury during angiography promote tissue factor release and systemic coagulation activation, even in the absence of large volumes of iodinated contrast [3].

Importantly, baseline fibrinogen concentration > 3.5 g/L was associated with a more pronounced rise in D-dimer (OR 2.1; 95% CI 1.3–3.5; p = 0.002), indicating that patients with an existing prothrombotic profile are more susceptible to post-procedural coagulation activation [5]. Previous evidence shows that elevated fibrinogen and D-dimer levels in patients with PAD and CKD predict worse outcomes, including higher rates of amputation and cardiovascular mortality [2]. Therefore, monitoring these parameters may be clinically useful for identifying patients at increased thrombotic risk following endovascular interventions.

Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Responses

In parallel with hemostatic activation, inflammatory and oxidative stress markers increased significantly after angiography. hs-CRP rose from 4.8 ± 2.2 mg/L to 6.5 ± 2.9 mg/L (p < 0.001) at 24 hours, IL-6 increased from 7.4 ± 3.1 pg/mL to 10.8 ± 4.5 pg/mL (p < 0.001), and MDA levels, reflecting lipid peroxidation, rose from 2.4 ± 0.6 µmol/L to 3.0 ± 0.7 µmol/L (p < 0.001). Although these parameters declined slightly at 72 hours, they remained significantly elevated compared to baseline. This suggests a transient but systemic inflammatory and oxidative response induced by vascular instrumentation and reperfusion [12].

Several studies have shown that increased oxidative stress and inflammatory activation contribute to endothelial dysfunction and renal tubular injury, serving as key mediators of contrast-induced nephropathy and related vascular complications [13]. In this context, even though CO₂ lacks direct chemical nephrotoxicity, procedure-related inflammation and oxidative stress may account for residual renal impairment. The interplay between coagulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress likely represents a unified pathogenic mechanism driving microvascular and renal dysfunction in patients with CKD and CLI.

Clinical Implications

Our findings support the clinical utility of CO₂ angiography as a safer contrast alternative for patients with CKD and CLI. However, clinicians should recognize that renal and systemic perturbations can still occur, particularly among patients with pre-existing proinflammatory or prothrombotic states. A multimodal prevention strategy—limiting total contrast volume, optimizing hydration, avoiding nephrotoxic agents, and possibly attenuating inflammation and oxidative stress through pharmacologic means (e.g., statins, antioxidants)—may further mitigate risk [14].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The cohort consisted exclusively of retired military patients, mostly male, which may limit external validity. The absence of a randomized iodinated-contrast control group precludes direct causal comparison. Follow-up was limited to 72 hours; thus, we did not assess long-term renal recovery or cardiovascular outcomes. Moreover, we did not include tubular injury biomarkers (e.g., NGAL, KIM-1) or assess microcirculatory renal perfusion changes, which might have provided additional mechanistic insight.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CO₂-based angiography demonstrated favorable renal safety compared with traditional iodinated contrast in high-risk patients with CLI and CKD, yet was associated with measurable transient declines in renal function and activation of hemostatic, inflammatory, and oxidative pathways. Baseline prothrombotic and inflammatory status and total contrast volume independently predicted the magnitude of these changes. These findings underscore that while CO₂ angiography reduces risk, it does not eliminate it, and careful patient selection, procedural optimization, and post-procedural monitoring remain crucial.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the Military Medical Academy of the Armed Forces for their invaluable technical assistance and patient care during the study.

- Komaba C, Komaba H, Imagawa K. (2025). Chronic limb-threatening ischemia in patients undergoing hemodialysis: epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Atheroscler Thromb.

- Serra R, Aboyans V, Diehm C. (2021). The impact of chronic kidney disease on peripheral artery disease and lower limb revascularization. Int J Gen Med. 14: 2829-2844.

- Miceli G, Barbieri SS. (2022). The role of the coagulation system in peripheral arterial disease. Int J Mol Sci. 23(3): 14914.

- Hazae BA, Hernaningsih Y, Wardhani P. (2024). Abnormalities in hemostatic parameters related to hemodialysis in end-stage kidney pathology: a narrative review. Pharmacogn J. 16(5): 1223-1230.

- Khan H, Patel K, Clements A. (2025). Current prognostic biomarkers for peripheral arterial disease: a review of circulating proteins and their clinical implications. Metabolites. 15(4): 224.

- Wittig T, Behrendt C-A, Rosch R. (2025). Acute kidney injury after peripheral interventions using carbon dioxide angiography in patients with peripheral artery disease and renal impairment. Lifetimes.15(7): 1046.

- Lee SR, Cohnert N-M, Fischer L. (2023). Carbon dioxide angiography during peripheral vascular interventions in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Vasc Surg. 78(5): 1443-1451.

- Khairy H, Balbaa S, Hefnawy E, Elmahdy H, Fekry K. (2021). Safety and efficacy of carbon dioxide angiography in the endovascular management of critical limb ischemia patients with renal insufficiency. J Clin Diag Res. 12(4): OC17-OC22.

- Ueda E, Ishiga K, Wakui H. (2024). Lipoprotein Apheresis Alleviates Treatment-Resistant Peripheral Artery Disease Despite the Normal Range of Atherogenic Lipoproteins: The LETS-PAD Study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 31(10): 1370-1385.

- DiBartolomeo AD, Browder SE, Bazikian S. (2023). Medial arterial calcification score is associated with increased risk of major limb amputation. J Vasc Surg. 78(5): 1286-1291.

- Guimaraes M, Fischman A, Yu H. (2024). The RAVI registry: prospective, multicenter study of radial access in embolization procedures - 30 days follow up. CVIR Endovasc. 7(1): 15.

- de Bruin JL, Verhagen HJM. (2024). The 2024 European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Abdominal Aorto-iliac Artery Aneurysms: Cutting Edge or Just Another Update?. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 67(2): 190-191.

- Kim HJ, Jung CY, Kim HW. (2023). Proteinuria Modifies the Relationship Between Urinary Sodium Excretion and Adverse Kidney Outcomes: Findings From KNOW-CKD. Kidney Int Rep. 8(5): 1022-1033.

- Zhang Y, Chen G, Wang W, Jing Y. (2025). C-reactive protein to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio: an independent risk factor for diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes patients. Front Nutr. 12: 1537707.

Download Provisional PDF Here

PDF

p (1).png)

.png)

.png)