Research Article

Temozolomide Increases Histone Lysine Demethylase Activity in Breast Cancer Cells

- Dr. Tieli Wang

Corresponding author: Dr. Tieli Wang, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Department of Clinical Science, California State University Dominguez Hills, Carson, CA 90747.

Volume: 3

Issue: 1

Article Information

Article Type : Research Article

Citation : Bernal, R, Martinez, P, Hills, R, Wang, T. Temozolomide Increases Histone Lysine Demethylase Activity in Breast Cancer Cells. Journal of Medical and Clinical Case Reports 3(1). https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCCR/2026/JAN027140131

Copyright: © 2026 Tieli Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCCR/2026/JAN027140131

Publication History

Received Date

12 Jan ,2026

Accepted Date

26 Jan ,2026

Published Date

31 Jan ,2026

Abstract

While extensive research has focused on the DNA methylation induced by the anticancer drug temozolomide (TMZ), there remains a gap in our understanding of its potential to methylate proteins. In a previous study, we explored the therapeutic effects of TMZ on histone methylation in glioma U87 cells and triple-negative breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) and understood how TMZ affects protein levels through this mechanism. Specifically, we are interested in histone proteins because of their roles in DNA binding and gene regulation. We observed a significant change in histone methylation levels in glioma brain cancer cells, but did not obtain a conclusive result in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. In this research, we examined histone lysine demethylase activity following TMZ treatment in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. We observed increased histone methylase activity in MDA-MB-231 cells. The results demonstrated TMZ's anticancer activity at the protein level, as evidenced by increased histone demethylase activity in MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells. Elucidating the effects of TMZ on protein methylation may reveal novel therapeutic mechanisms beyond its well-established DNA-damaging activity.

Graphic Abstract

Keywords: Temozolomide, histone methylation, therapeutic benefit, histone lysine demethylase, triple negative breast cancer, epigenetic regulation

►Temozolomide Increases Histone Lysine Demethylase Activity in Breast Cancer Cells

Bernal, R1,2, Martinez, P1, Hills, R2, Wang, T1,2*

1Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, California State University Dominguez Hills, Carson, CA 90747.

2Department of Clinical Science, California State University Dominguez Hills, Carson, CA 90747.

Introduction

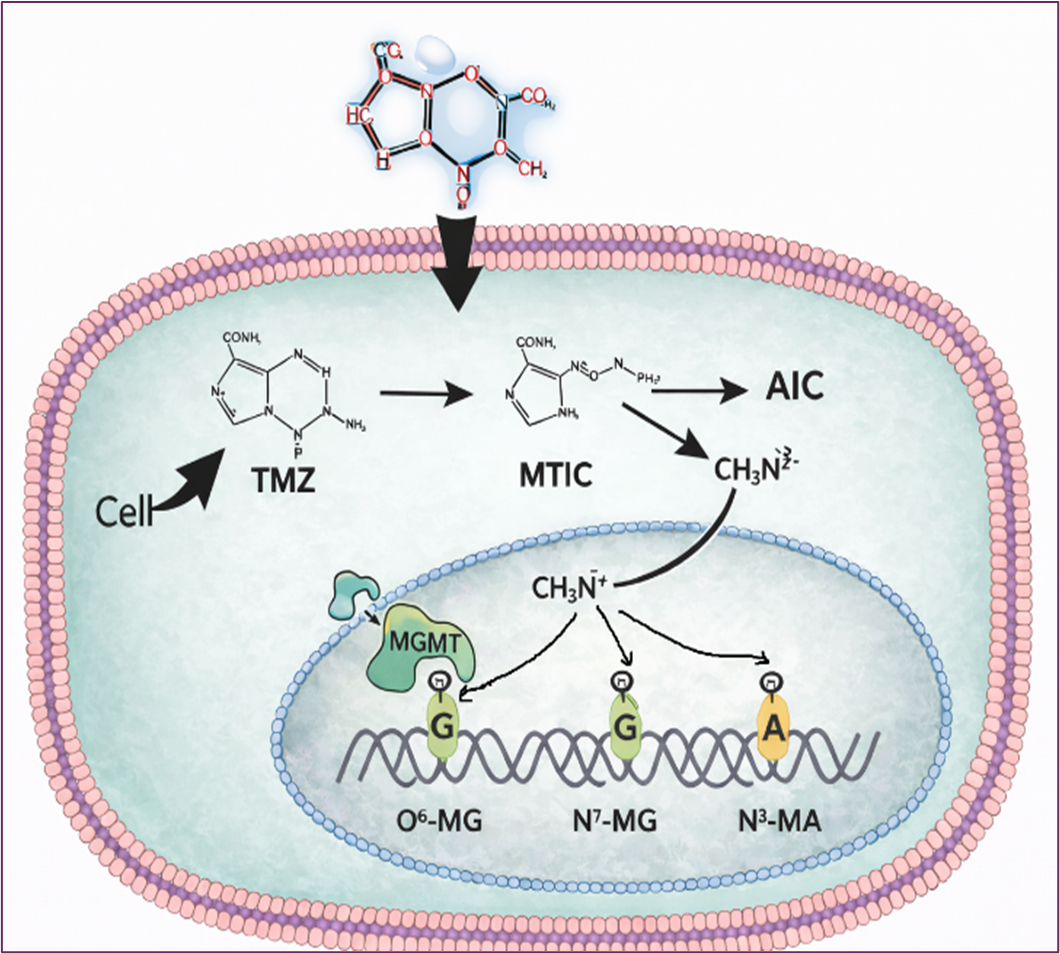

Temozolomide (TMZ) is a prototypical alkylating agent with well-established anticancer properties that exerts its therapeutic effects through DNA and protein methylation, functioning as a potent epigenetic regulator. As a prodrug, TMZ undergoes pH-dependent degradation through a well-characterized pathway: it first converts to 5-(3-methyltriazen-1-yl)imidazole-4-carboxamide (MTIC), which subsequently decomposes into 4-amino-5-imidazole-carboxamide (AIC)—an inactive metabolite—and a methyl-diazonium ion that serves as the primary methylating species (Figure 1).

The therapeutic potential of TMZ has been extensively characterized at the DNA level through genetic and molecular approaches. The methyl diazonium ion methylates DNA at multiple nucleophilic sites: approximately 70% at the N7 position of guanine, 9% at the N3 position of adenine, and critically, ~5% at the O6 position of guanine [1-2]. Although N7-methylguanine and N3-methyladenine adducts constitute the majority of lesions, they are efficiently repaired by base excision repair pathways and contribute minimally to cytotoxicity. In contrast, O6-methylguanine (O6-MeG) represents the principal cytotoxic lesion (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Cellular Process of TMZ At DNA-Levels Inside The Cells

During DNA replication, O6-MeG mispairs with thymine instead of cytosine, generating G:T mismatches. Futile cycles of mismatch repair trigger DNA double-strand breaks, genomic instability, cell cycle arrest, and ultimately apoptosis. [4-7]

Despite extensive characterization of TMZ-induced DNA modifications, its epigenetic effects at the protein level, particularly histone methylation and demethylation, remain largely unexplored. Histones are essential for maintaining chromosomal structural integrity and chromatin organization, and their post-translational modifications directly influence gene expression and genomic stability. Understanding how TMZ interacts with histones and their regulatory enzymes may provide valuable insights for developing targeted epigenetic therapies, particularly for treatment-resistant malignancies such as glioma and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). [8-18]

Our previous studies demonstrated that increasing TMZ concentrations altered histone methylation patterns in U87 glioma cells; however, this trend was not evident in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. [19-21] The present study aims to identify histone-modifying enzymes regulated by TMZ and establish their role at the protein level.

Materials And Methods

TMZ Preparation and Treatment

TMZ (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare a stock solution as described in a previous study. [21] Working concentrations of 100 µM were prepared by dilution in complete culture medium immediately prior to each experiment. The final DMSO concentration in all treatment wells did not exceed 0.1% (v/v) to minimize potential solvent-mediated cytotoxicity.

Culturing Cancer Cells for Experimental Assays

MDA-MB-231 (human breast adenocarcinoma, triple-negative) from ATCC was used in this study. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell culture medium was refreshed every 2-3 days, and cells were passaged upon reaching 80-90% confluence using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution.

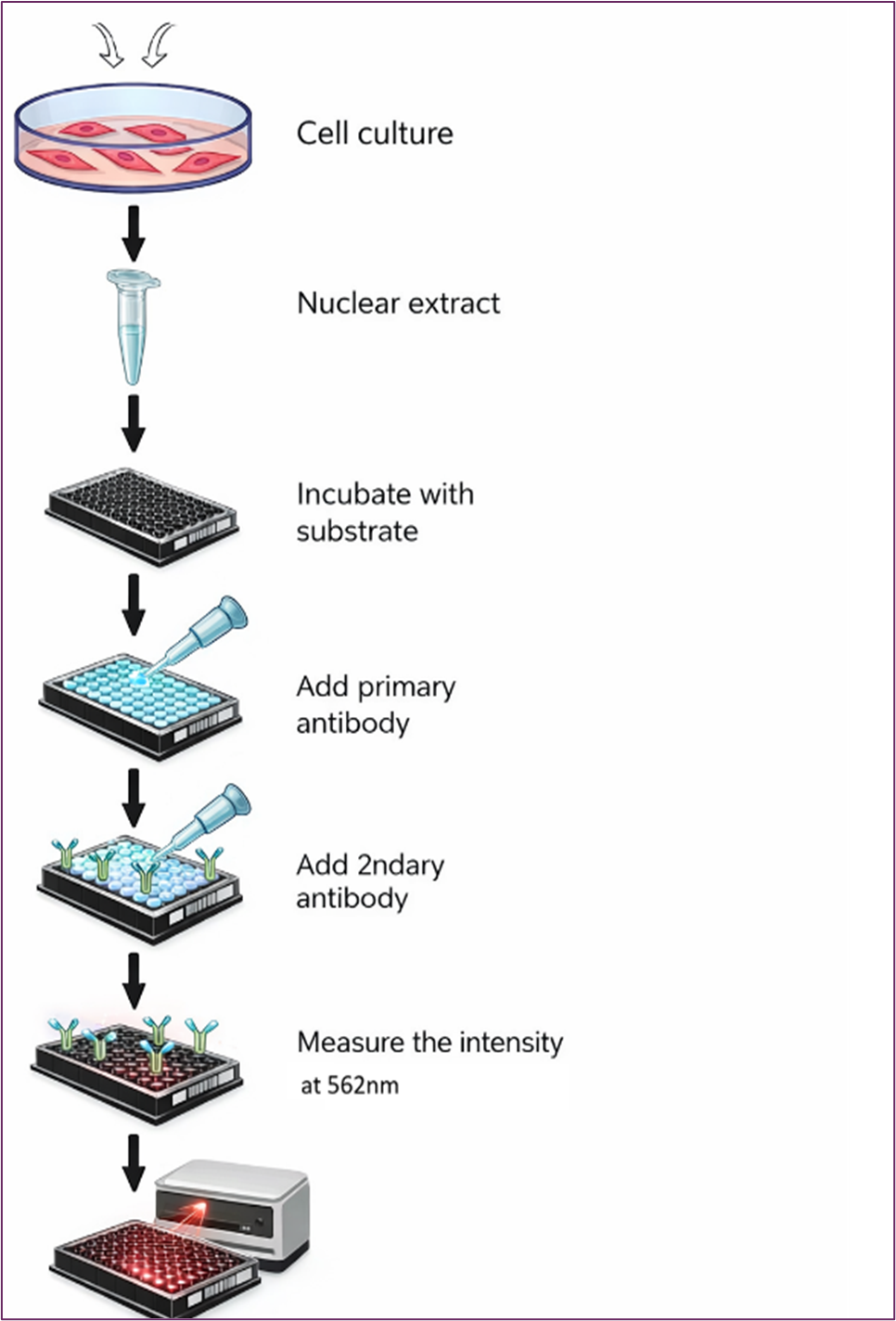

Nuclear Protein Extraction Assay

Nuclei were extracted using the nuclear protein extraction kit from EpigenTek (Catalog # OP-0002). 100ul DPNE1 buffer was added to each pellet (pre-extraction buffer – DPNE1). The sample was left on Ice for 10 minutes and then vortexed vigorously for 10 seconds. The solution was transferred to an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged for 1min at 12000rpm. The pellet was treated with 2 volumes of DPNE2 (extraction buffer DPNE2) and kept on Ice for 15min (vortex every 3 min, sonicate every 3 min for 10 seconds). The solution was then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 14000rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was assayed for protein concentration.

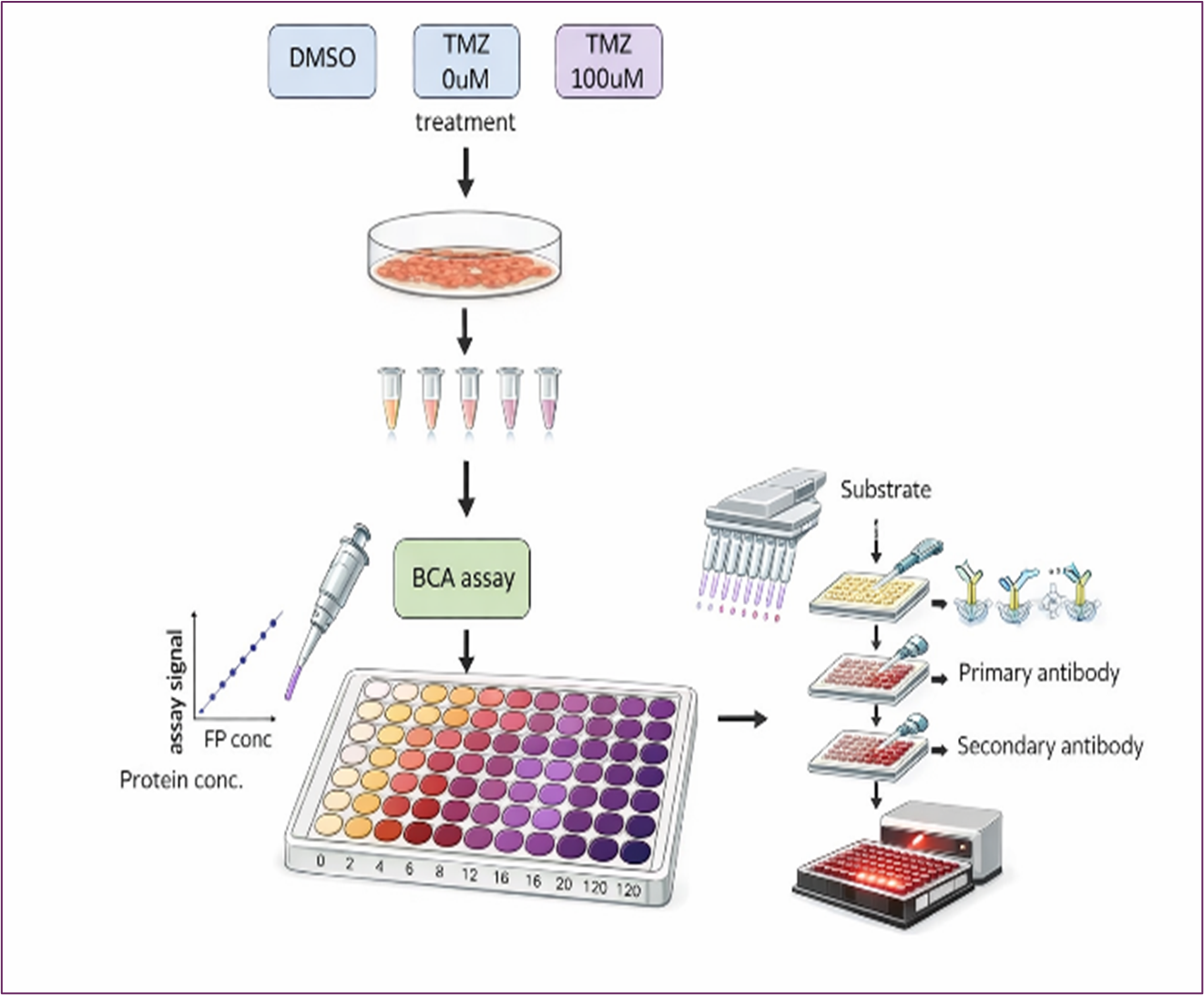

Protein Concentration Assay

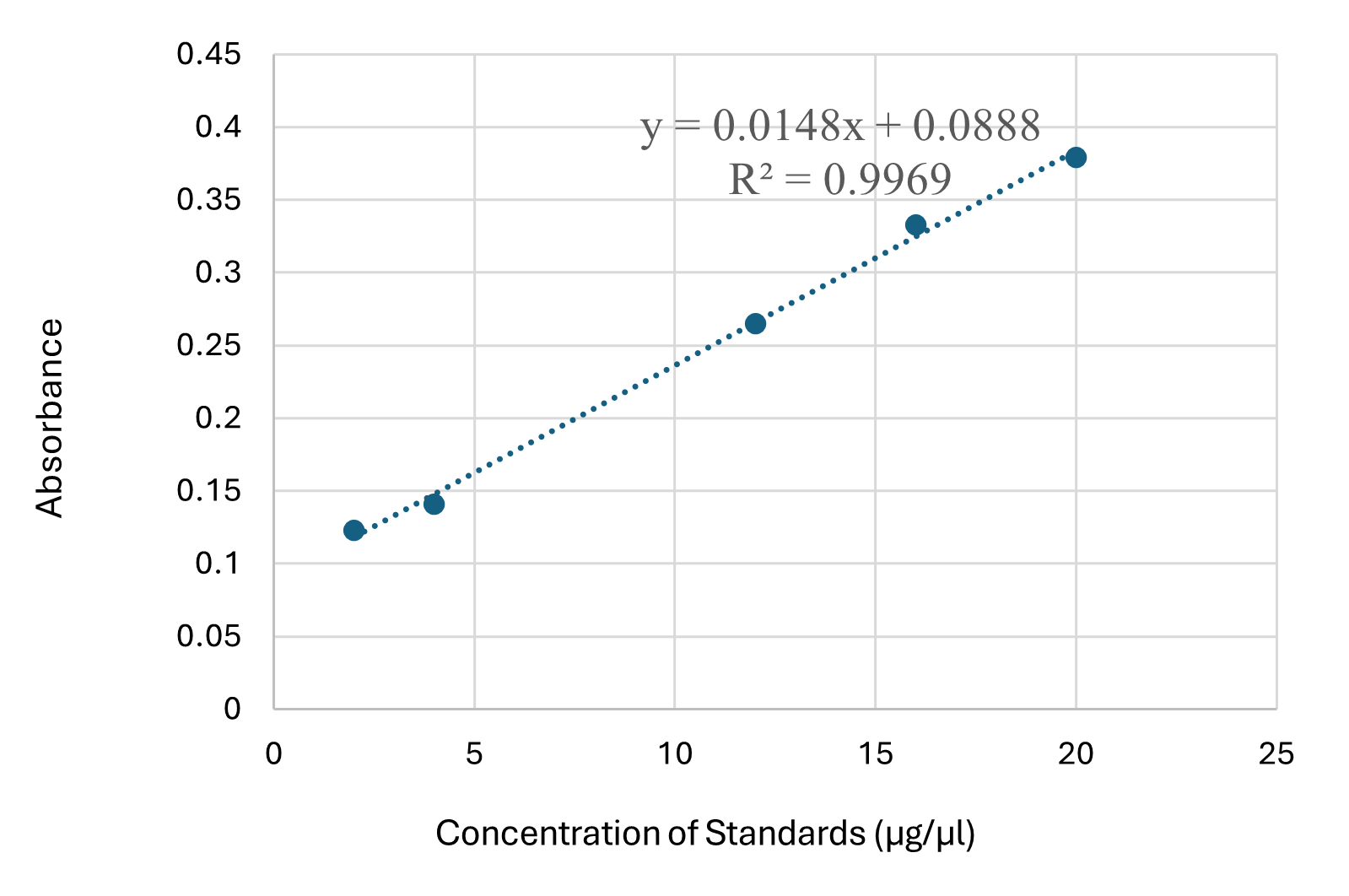

The bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay was used to determine the concentration of nuclear proteins. The working solution was prepared by mixing reagent A and reagent B in a 50:1 ratio. 100 μl working solution was added to each well, followed by 10 μl standard or sample in a 96-well plate. The standard samples were prepared at concentrations of 0, 2, 4, 12, 16, and 20 μg/μL. Both standards and samples were run in duplicate. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour, during which a violet color developed. Absorbance was measured at 562nm after the incubation using a BioTek ELx 808 plate reader. The linear regression equation was obtained by plotting concentration (x-axis)) against absorbance (y-axis). The concentration of the samples was then calculated using the linear regression equation. 5-20 μg of nuclear protein was used for the demethylase activity assay. 10ug level is the optimized condition.

Lysine-Specific Histone Demethylase (LSD1) Activity Assays

The assay is performed using commercially available assay kit from EpigenTek (Catalog # P-3078). 96-well plates were employed to evaluate the effects of TMZ on histone demethylase activity. The assay uses antibodies specific to methylated histones to quantify methylation. We tested histone lysine demethylase (LSD1) targeting histone H3 at lysine 4 following TMZ treatment in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. The assay kit provides all the essential reagents for a successful LSD1 activity/inhibition experiment. Each well in the 96 plates contained substrates at varying concentrations, with different concentrations of LSD1 enzyme, both in the presence or absence of TMZ. After an incubation period of 1 to 2 hours, the methylated histone H3K4 was recognized with a high-affinity antibody. The amount of methylated histone is directly proportional to enzyme activity. Measurements were taken using BioTek ELx 808 plate reader. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (about 3000 cells/well). Figure 2 depicts the demethylase assay procedures as described in the manufacturer's manual. The study included the following treatment groups

- DMSO group: breast cancer cells treated with DMSO

- Control group: breast cancer without treatment

- Treatment group: Cells treated with 100μM of TMZ

The LSD1 activity was assessed after 48 hours following TMZ treatment. Every study was performed in duplicate.

Figure 2. Diagram for Evaluating the Effects of TMZ on Histone Demethylase Activity

Results

Nuclear Protein Extraction

Nuclear proteins located inside the nuclei of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were extracted. The Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) Protein Assay was used to quantify nuclear protein concentration using the method described in a previous report. [21]

The linear regression analysis yielded the equation Y = 0.0148x + 0.0888, with R^2 = 0.9969, relating the concentration of the standard (x) to its absorbance (y), as shown in Table 1 and Figure 3.

Figure 3. Linear Regression Analysis of Standard Samples

Table 2 displays the average sample concentration calculated using this equation, along with the corresponding plot shown in Figure 3.

Table 1. Absorbance Measurement of Standard Solution

|

Concentration of Standard (μg/ul) |

Absorbance of Standard |

|

0 |

0.072 |

|

0 |

0.075 |

|

2 |

0.123 |

|

4 |

0.141 |

|

12 |

0.265 |

|

16 |

0.333 |

|

20 |

0.379 |

Table 2. Nuclear Protein Concentration of Breast Cancer Cells Following the TMZ Treatment

|

Samples |

Absorbance of the Sample |

Concentration of Sample (μg/μl) |

|

DMSO |

0.204 |

7.78 |

|

0 μM TMZ |

0.255 |

11.23 |

|

100μM TMZ |

0.149 |

4.07 |

TMZ Enhances Histone Lysine Demethylase Activity

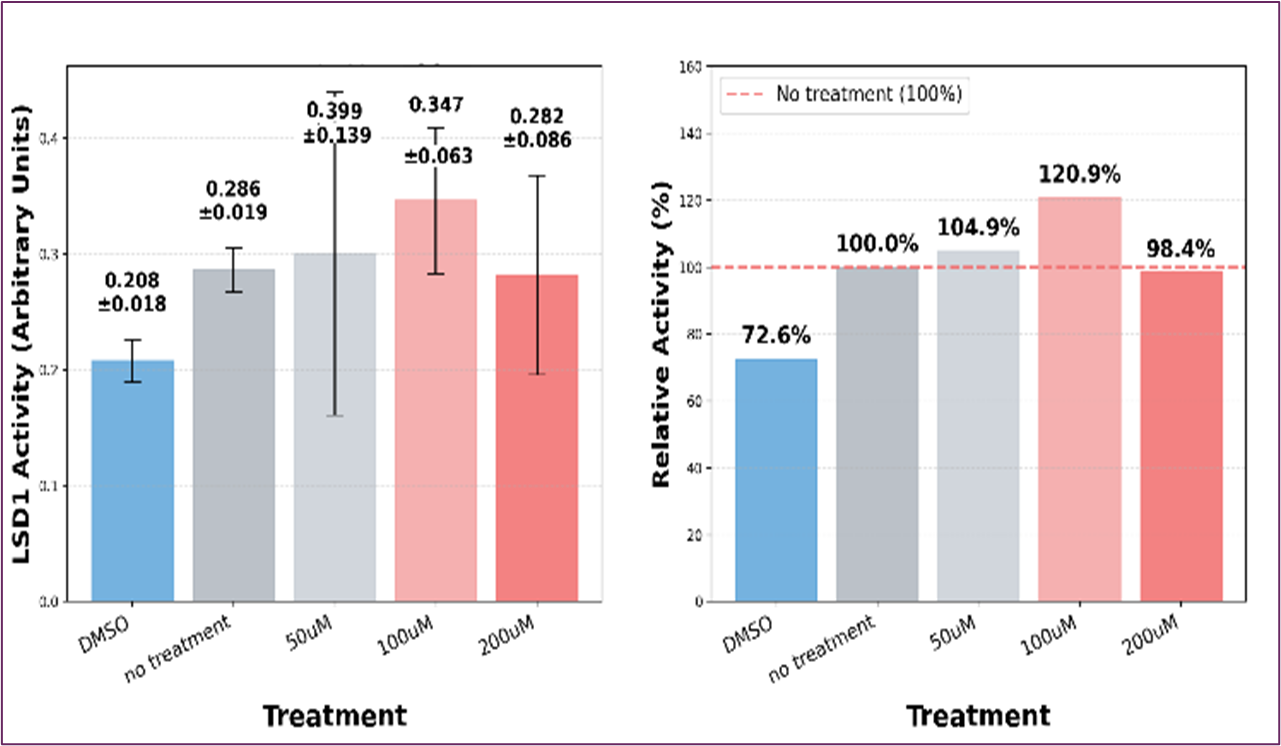

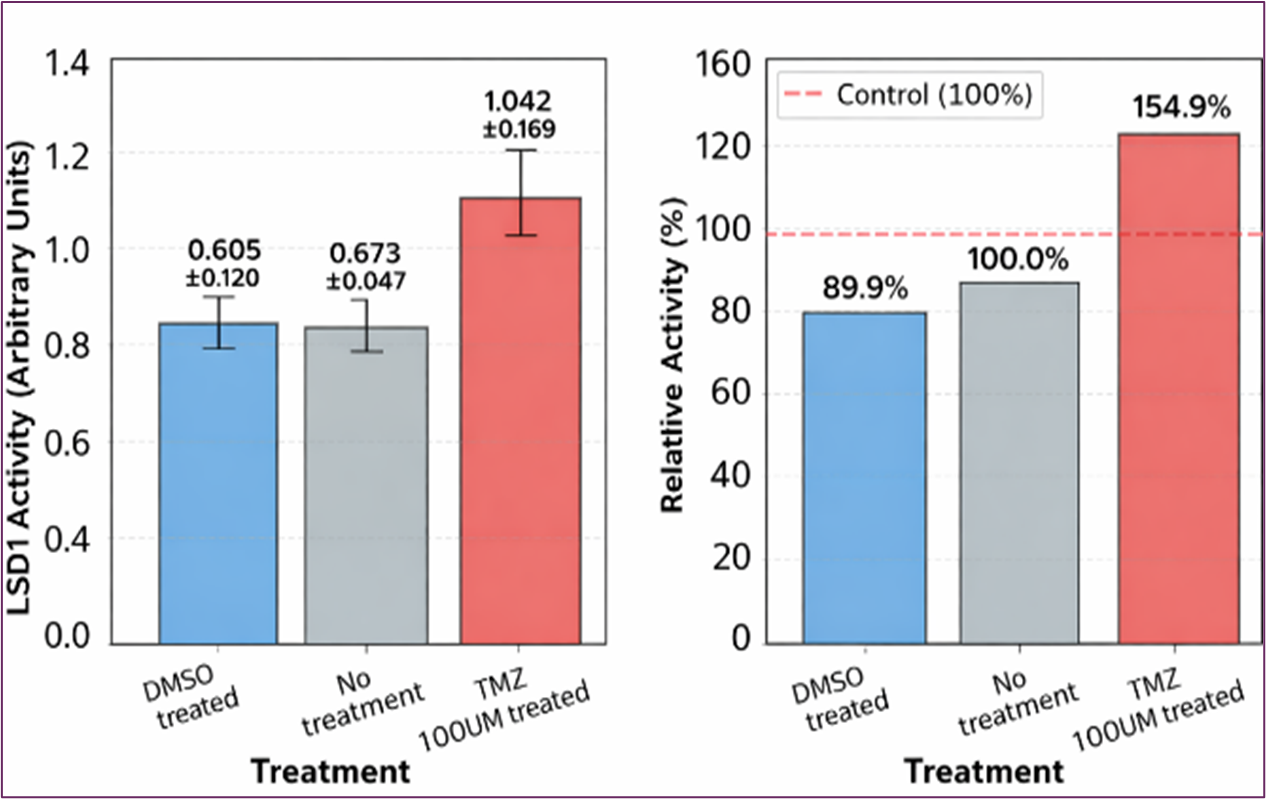

Identifying the molecular targets responsible for TMZ's therapeutic effects remains a significant challenge. Histones represent attractive candidates for TMZ-mediated methylation due to their central roles in chromatin organization and gene regulation, as well as their dynamic post-translational modification landscape. Our previous studies on TNBC breast cancer did not obtain a conclusive result regarding histone methylation levels by TMZ. [21] We therefore examined whether TMZ, through its active metabolite methyl-diazonium, could directly modify histone-associated proteins in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. To test this hypothesis, we measured histone lysine demethylase (LSD1) activity following TMZ treatment. The initial experiment was conducted using a range of TMZ concentrations spanning 0 to 200 μM. The results of an experiment examining histone demethylase activity under different treatment conditions are shown in Figure 4 (DMSO vehicle control, no treatment (0 μM), 50 μM, 100 μM, and 200 μM TMZ). A non-linear dose response with peak activity of LSD1 was observed. We repeated the experiment under 100 μM TMZ treatment. The results showed that TMZ has a stimulatory effect on LSD1 activity compared to the DMSO vehicle control and untreated cancer cells at 100uM concentrations, as shown in Figure 5. The substantial LSD1 activation by TMZ is an interesting finding that could have implications for understanding TMZ’s mechanism of action, particularly given LSD1’s role in chromatin remodeling and gene regulation.

These findings reveal an intriguing difference in TMZ's epigenetic effects. While our previous studies showed that TMZ directly reduces histone methylation levels in glioblastoma cells. In contrast, similar effects were not conclusively observed in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. However, the increase in histone demethylase activity following TMZ treatment in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells suggests that histone methylation regulation involves a multifaceted regulatory network. We propose that TMZ may methylate or activate histone demethylases in MDA-MB-231 cells. Through either the direct methylation mechanism or the indirect activation pathway, TMZ can effectively alter histone methylation patterns and chromatin architecture.

Figure 4. Dose-Response Analysis of LSD1 Activity

Figure 5. Results of Histone Lysine Demethylase (LSD1)

Discussion

Our previous studies examined the effects of TMZ on histone methylation levels in TNBC MDA-MB-231 and did not yield conclusive results. We plan to further confirm these results by using more reliable Western blot equipment in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. [21] The current study examined whether TMZ exerts its effects on histone-associated enzymes. The preliminary results showed a promising increase in LSD1 activity with TMZ at a 100uM concentration, supporting the concept that TMZ exerts anticancer effects through protein-level epigenetic modifications that extend beyond its well-established DNA-damaging effects. Furthermore, these results suggest that intrinsic differences in cellular epigenetic machinery may critically influence how tumors respond to alkylating agents.

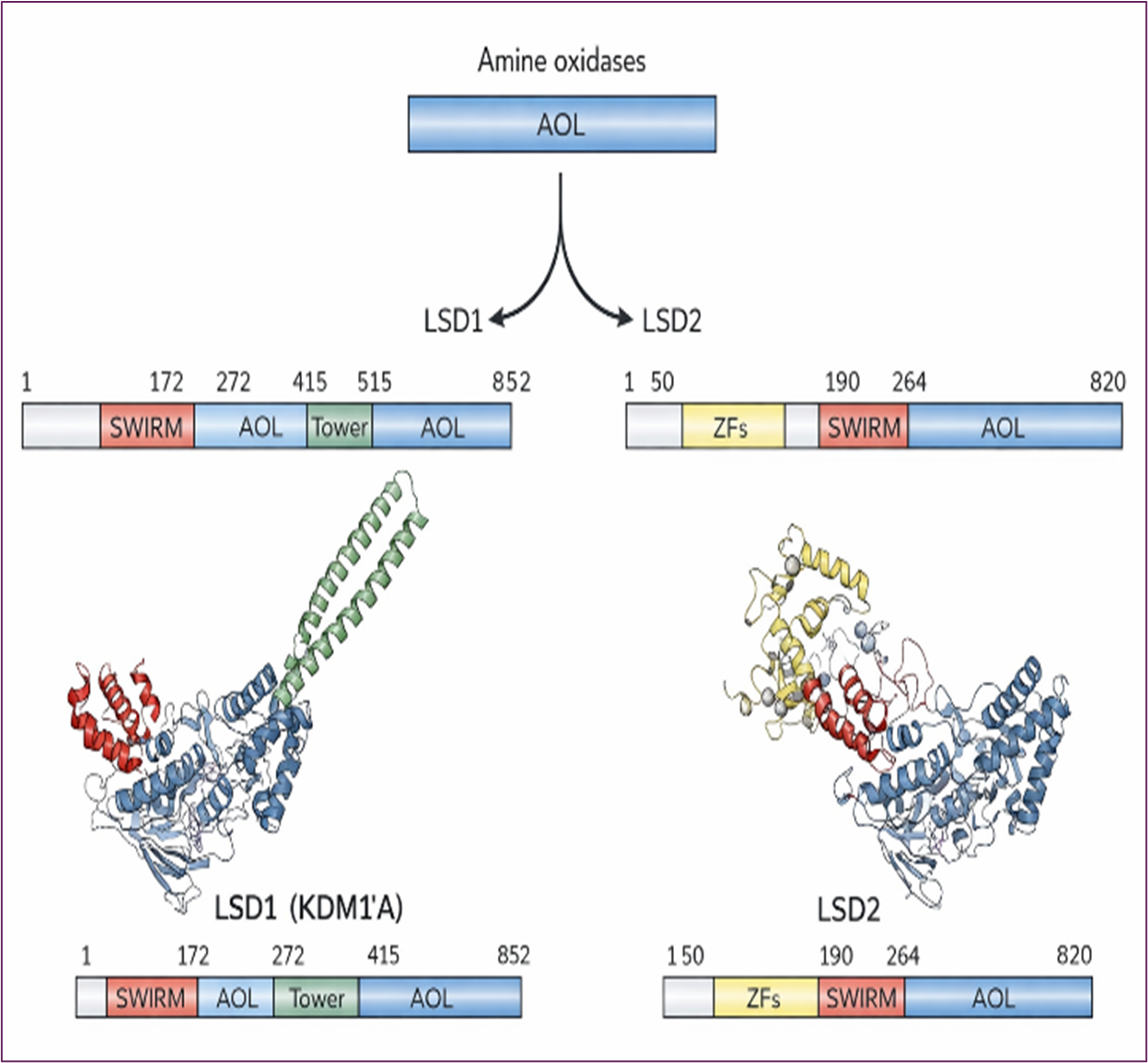

Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) has emerged as a validated therapeutic target due to its overexpression across multiple cancer types. LSD1 modulates gene expression by catalyzing the removal of methyl groups from specific histone lysine residues (H3K4me1/2 and H3K9me1/2), thereby altering chromatin structure and gene accessibility. The LSD family comprises two members—LSD1 and —both characterized by a conserved amine oxidase-like (AOL) domain (Figure 6). LSD1 (also known as KDM1A), first identified in 2004, specifically demethylates mono- and di-methylated lysine residues at histone H3 lysine 4 and lysine 9 (H3K4me1/2 and H3K9me1/2) [22-24].

Figure 6. Structure Overview for Lysine-specific Demethylase (LSD) Family

Methylation of histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) by LSD1 is an important epigenetic mark and is significant for the regulation of cellular processes, as it is associated with active regions of the genome. This methylation was considered irreversible until the identification of numerous histone demethylases indicated that demethylation events play an important role in histone modification dynamics. LSD1 can demethylate mono- and di- methylated lysine residues on H3K4 but cannot remove trimethylated H3K4 due to mechanistic constraints.

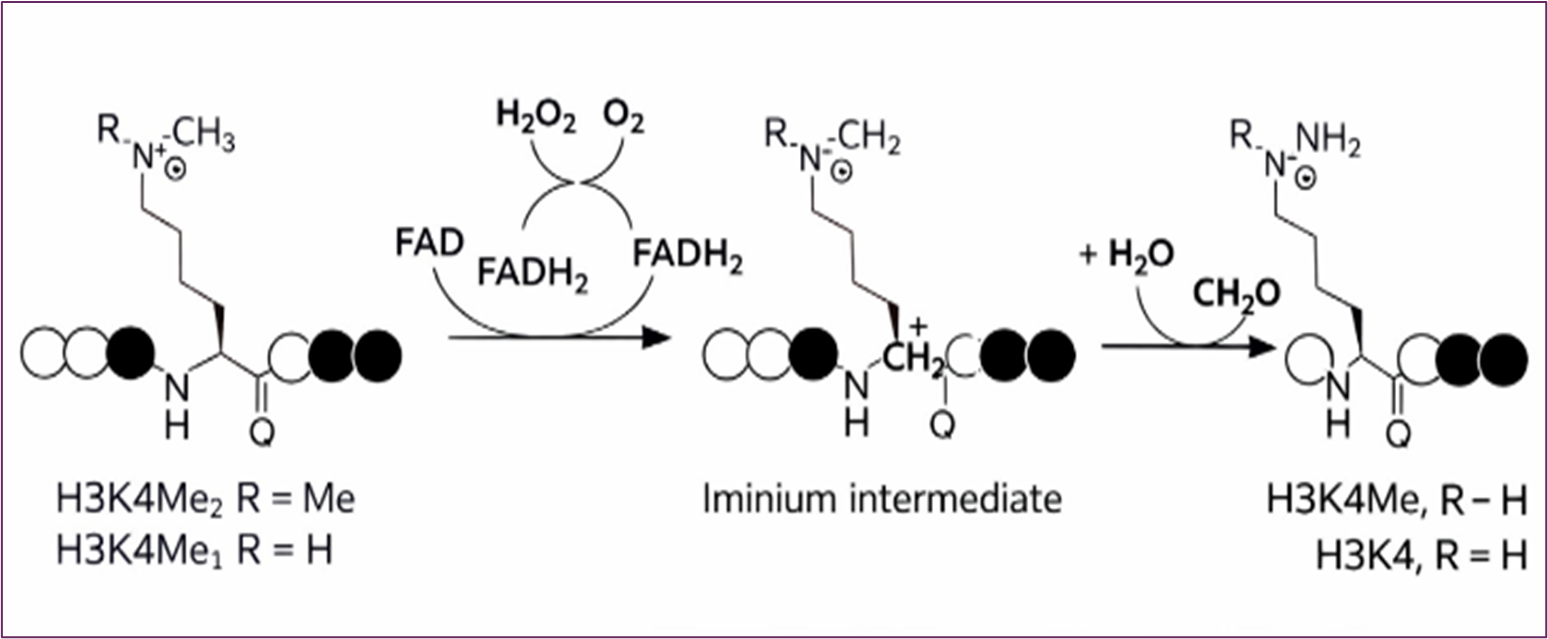

LSD1 employs a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)-dependent oxidation mechanism to catalyze demethylation. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) catalyzes the oxidative demethylation of mono- and di- methylated H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me1/2) through an FAD-dependent mechanism. Oxidation of the ε-methylated lysine generates an iminium intermediate, which undergoes hydrolysis to release formaldehyde and yield demethylated lysine. Reduced FADH₂ is reoxidized by molecular oxygen, producing hydrogen peroxide. (Figure 7) [25-28].

Figure 7. LSD Enzymatic Mechanism - FAD-Dependent Lysine Demethylation Mediated by LSD1

Histone lysine methylation and demethylation represent critical mechanisms of epigenetic regulation in cancer, with lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) emerging as a central mediator of TMZ's epigenetic effects in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. Beyond its canonical histone substrates, LSD1 regulates several critical non-histone proteins, including DNMT1, p53, STAT3, and E2F1 [29-30], positioning it as a master regulator of gene expression and cellular phenotypes. Importantly, LSD1's functional output is highly context-dependent: when complexed with CoREST or nucleosome remodeling complexes, it acts as a transcriptional repressor, whereas association with androgen or estrogen receptors confers transcriptional activator function [31-32]. This dual functionality underscores LSD1's versatility as an epigenetic regulator and highlights the complexity of TMZ's protein-level mechanisms beyond its well-established DNA-damaging effects.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the LSAMP program and the CSUDH course-related funding support. The author appreciates the assistance and discussions from AI assistance during the document editing process.

Conclusion

Elucidating the mechanism by which temozolomide (TMZ) exerts its therapeutic efficacy is essential for advancing cancer treatment strategies. Recent investigations have identified histones—key regulators of DNA packaging and gene expression—as potential targets for TMZ-mediated methylation, given their dynamic post-translational modification profiles. This study demonstrates that the therapeutic benefits of TMZ extend beyond DNA to the protein level, specifically by enhancing histone demethylase activity.

Our previous experiment did not yield a conclusive result regarding the effect of TMZ on histone methylation levels in MDA-MB-231 cells; the current findings reveal that TMZ increased histone lysine demethylase activity in TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells. Collectively, this study provides preliminary yet promising evidence supporting TMZ activity at the protein level and warrants further mechanistic investigation to establish its therapeutic potential in cancer cells.

- Danson SJ, Middleton MR. (2001). Temozolomide: a novel oral alkylating agent. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 1(1): 13-19.

- Lopes IC OS, Oliveira-Brett AM. (2013). In situ electrochemical evaluation of anticancer drug temozolomide and its metabolites-DNA interaction. Anal Bioanal Chem. 405(11): 3783-3790.

- Klose RJ, Bird AP. (2006). Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 31(2): 89-97.

- Roos WP, Kaina B. (2013). DNA damage-induced cell death: from specific DNA lesions to the DNA damage response and apoptosis. Cancer Lett. 332(2): 237-248.

- Kaina B. (2023). Temozolomide, Procarbazine and Nitrosoureas in the Therapy of Malignant Gliomas: Update of Mechanisms, Drug Resistance and Therapeutic Implications. J Clin Med. 12(23): 7442.

- Jezierzański, M. (2024). Temozolomide (TMZ) in the Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme - A Literature Review and Clinical Outcomes. Current Oncology. 31(7): 3994–4002.

- Strobel, H, Baisch T, Fitzel, R, Schilberg, K, Siegelin, M.D, Karpel-Massier, G, Debatin, KM, and Westhoff, MA. (2019). Temozolomide and Other Alkylating Agents in Glioblastoma Therapy. Biomedicines. 7(3): 69.

- Füllgrabe J, Hajji N, Joseph B. (2010). Cracking the death code: apoptosis-related histone modifications. Cell Death Differ. 17(8): 1238-1243.

- Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. (2007). Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol.Cell. 25(1): 15-30.

- Shilatifard A. (2008). Molecular implementation and physiological roles for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 20(3): 341-348.

- Kouzarides T. (2002). Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 12(2): 198-209.

- Martin C, Zhang Y. (2005). The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 6(11): 838-849.

- Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. (2012). Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell. 48(4): 491-507.

- Handel AE, Ebers GC, Ramagopalan SV. (2010). Epigenetics: molecular mechanisms and implications for disease. Trends Mol Med. 16(1): 7-16.

- Rajan PK, Udoh UA, Sanabria JD. (2020). The Role of Histone Acetylation-/Methylation-Mediated Apoptotic Gene Regulation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 21(23): 8894.

- Yu H, Lesch BJ. (2024). Functional Roles of H3K4 Methylation in Transcriptional Regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 44(11): 505-515.

- Wang H, Helin K. (2025). Roles of H3K4 methylation in biology and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 35(2): 115-128.

- Strahl, B.D. and Allis, C.D. (2000) The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 403(6765): 41-45.

- Wang, T, Pickard, A. and Gallo, J. (2016). Histone methylation by temozolomide; a classic DNA methylating anticancer drug. Anticancer Research. 36(7): 3289 – 3300.

- Wang, T. (2017). Proteomics for post-translational modification studies of histone and its implication in brain cancer therapeutic development. European Cancer Summit. Innovinc International publisher. 13.

- Martinez, P, Bernal, R, Hills, R, and Wang, T. (2024). Investigating the Therapeutic Effects of Temozolomide Through Histone Methylation Analysis. Journal of Medical and Clinical Case Reports. 1(8).

- Perillo, B, Tramontano, A, Pezone, A. (2020). LSD1: more than demethylation of histone lysine residues. Exp Mol Med. 52: 1936–1947.

- Rudolph T, Beuch S, Reuter G. (2013). Lysine-specific histone demethylase LSD1 and the dynamic control of chromatin. Biol. Chem. 394: 1019–1028.

- Forneris F, Battaglioli E, Mattevi A, Binda C. (2009). New roles of flavoproteins in molecular cell biology: histone demethylase LSD1 and chromatin. FEBS J. 276(16): 4304-4312.

- Barciszewska, A.-M, Gurda, D, Głodowicz, P, Nowak, S, Naskr˛et-Barciszewska, M.Z. (2015). A New Epigenetic Mechanism of Temozolomide Action in Glioma Cells. PLoS ONE. 10: 0136669.

- Højfeldt, J. W, Agger, K Helin, K. (2013). Histone lysine demethylases as targets for anticancer therapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 12(12): 917–930.

- Perillo, B, Tramontano, A, Pezone, A. (2020). LSD1: more than demethylation of histone lysine residues. Exp Mol Med. 52: 1936–1947.

- Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD. (2009). Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 459(7243): 108-112.

- Lee MG, Wynder C, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. (2005). An essential role for CoREST in nucleosomal histone 3 lysine 4 demethylation. Nature. 437(7057):432-5.

- Carpenter BS, Scott A, Goldin R, Chavez SR, Rodriguez JD, Myrick DA, Curlee M, Schmeichel KL, Katz DJ. (2023). SPR-1/CoREST facilitates the maternal epigenetic reprogramming of the histone demethylase SPR-5/LSD1. Genetics. 223(3): iyad005.

- Magliulo D, Bernardi R, Messina S. (2018). Lysine-Specific Demethylase 1A as a Promising Target in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front Oncol. 8: 255.

- Hartung EE, Singh K, Berg T. (2023). LSD1 inhibition modulates transcription factor networks in myeloid malignancies. Front Oncol. 13: 1149754.

Download Provisional PDF Here

PDF

p (1).png)

.png)

.png)