Mini Review Article

Mechanisms of Poor Fetal Hemoglobin (Hb F) Induction by Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia: A Review

- Khalid Abdelsamea Mohamedahmed

Corresponding author: Khalid Abdelsamea Mohamedahmed, Department of Immunology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Gezira, Wad Medani, Sudan. ORCID No: 0000-0001-7084-6106.

Volume: 3

Issue: 1

Article Information

Article Type : Mini Review Article

Citation : Khalid Abdelsamea Mohamedahmed, Mechanisms of Poor Fetal Hemoglobin (Hb F) Induction by Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia: A Review. Journal of Medicine Care and Health Review 3(1). https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCHR/2026/JAN027140123

Copyright: © 2026 Khalid Abdelsamea Mohamedahmed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.61615/JMCHR/2026/JAN027140123

Publication History

Received Date

03 Jan ,2026

Accepted Date

17 Jan ,2026

Published Date

23 Jan ,2026

Abstract

Hydroxyurea (HU) is the cornerstone pharmacologic agent for inducing fetal hemoglobin (Hb F) in sickle cell disease (SCD) and β-thalassemia. Although it has demonstrated substantial clinical benefits, a subset of patients exhibits suboptimal Hb F response, limiting its therapeutic efficacy. This mini-review summarizes current knowledge on the mechanisms of poor Hb F induction with HU, focusing on genetic polymorphisms in key quantitative trait loci (BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and HBG2), epigenetic regulation of γ-globin gene expression, and pharmacokinetic variability driven by differences in drug metabolism and clearance. We also discuss the clinical implications of these resistance mechanisms and potential strategies to enhance HU responsiveness, including precision medicine approaches and emerging adjunct therapies. Understanding these factors is essential for optimizing Hb F induction and improving outcomes in hemoglobinopathies.

►Mechanisms of Poor Fetal Hemoglobin (Hb F) Induction by Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Disease and β-Thalassemia: A Review

Khalid Abdelsamea Mohamedahmed1,2,3*

1Department of Hematology and Immunohematology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Gezira, Wad Medani, Sudan.

2Department of Immunology, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, University of Gezira, Wad Medani, Sudan. ORCID No: 0000-0001-7084-6106.

3Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Jerash University, Jerash, Jordan.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) and β-thalassemia are among the most prevalent inherited hemoglobinopathies worldwide, contributing significantly to global morbidity and mortality, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia [1,2]. SCD results from a point mutation in the β-globin gene (HBB), leading to sickle hemoglobin (Hb S) production, erythrocyte sickling, vaso-occlusion, and chronic hemolysis [3,4]. β-Thalassemia arises from mutations causing reduced or absent β-globin synthesis, resulting in ineffective erythropoiesis, anemia, and iron overload due to transfusion dependence [5].

Fetal hemoglobin (Hb F; α₂γ₂) has long been recognized as a major disease modifier. Its continued expression inhibits Hb S polymerization and ameliorates the ineffective erythropoiesis of β-thalassemia [6,7]. Patients with elevated Hb F levels due to hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH) or pharmacologic induction often experience fewer complications and better survival outcomes [8].

Hydroxyurea (HU) is the first and only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy for SCD and is widely used off-label in β-thalassemia intermedia [9]. HU increases Hb F by inducing stress erythropoiesis, altering erythroid differentiation, and potentially affecting nitric oxide signaling and γ-globin gene activation [10-13]. Clinical trials have demonstrated that HU reduces painful crises, acute chest syndrome, and transfusion needs while improving survival in SCD [14,15]. However, inter-patient variability in HU response remains a major clinical challenge, with approximately 20–30% of patients demonstrating suboptimal Hb F induction [16,17].

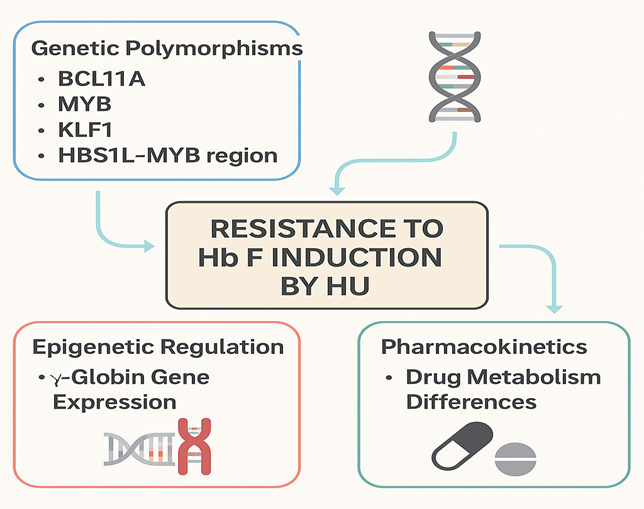

This variability in response is multifactorial. Genetic determinants, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and the XmnI site (−158 C>T), influence baseline Hb F levels and response to HU [18,19]. Epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications maintain γ-globin silencing and may limit HU’s efficacy [20,21]. Furthermore, microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as key post-transcriptional regulators of γ-globin gene expression [22]. Pharmacokinetic factors, influenced by polymorphisms in genes such as CYP2D6, CAT, and SLC14A1, can also affect HU bioavailability and therapeutic outcomes [23,24].

This mini-review explores these mechanisms of HU resistance and highlights current and future strategies to overcome them.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of Resistance to Hb F Induction by Hydroxyurea

Discussion

1. Genetic Determinants of HU Response

Genetic polymorphisms in Hb F-associated loci significantly influence HU response. Variants in BCL11A, a key γ-globin repressor, are strongly associated with higher baseline Hb F levels and improved HU responsiveness [18]. Similarly, SNPs in the HBS1L-MYB intergenic region modulate erythroid differentiation and Hb F expression [19]. The XmnI (−158 C>T) polymorphism upstream of HBG2 correlates with enhanced Hb F production in response to HU [20]. Studies have also implicated genes involved in stress erythropoiesis, such as ARG1, SAR1A, and NOS1, though findings remain heterogeneous [21].

2. Epigenetic and Transcriptional Regulation

Epigenetic repression of γ-globin genes involves DNA methylation and histone deacetylation. HU may partially reverse these modifications by inducing stress erythropoiesis and activating pathways that downregulate repressors such as BCL11A and KLF1 [22]. miRNAs, including miR-15a, miR-26b, and miR-151-3p, have been identified as mediators of γ-globin reactivation via suppression of these transcriptional repressors [23]. However, inter-individual differences in epigenetic regulation may underlie resistance in some patients.

3. Pharmacokinetic Variability

HU bioavailability and metabolism vary widely among individuals. Polymorphisms in CYP2D6, CAT, and SLC14A1 can affect drug absorption, distribution, and clearance [24,25]. Rapid metabolism or poor absorption may lead to subtherapeutic HU levels, contributing to poor Hb F induction. Population pharmacokinetic models support the potential for genotype-guided HU dosing strategies to optimize therapy [26].

4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The identification of genetic and epigenetic biomarkers for HU responsiveness has enabled the development of predictive algorithms to guide personalized therapy. Adjunct treatments, such as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (decitabine) and histone deacetylase inhibitors, are under investigation to augment HU-induced Hb F production [27]. Gene-editing technologies targeting BCL11A and other repressors represent promising avenues for achieving sustained Hb F induction in poor HU responders [28].

Conclusion

Poor Hb F induction with HU therapy in SCD and β-thalassemia is a complex phenomenon involving genetic, epigenetic, and pharmacokinetic factors. A precision medicine approach incorporating predictive genomics and pharmacogenetics may improve treatment outcomes. Further research into adjunct therapies and novel agents targeting Hb F repression pathways holds promise for patients who are resistant to HU.

- Piel FB, Patil AP, Howes RE, Nyangiri OA, Gething PW, Dewi M. (2013). Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet. 381(9861): 142–151.

- Elshaikh RH, Amir R, Ahmeide A, Mohamedahmed KA. (2022). Evaluation of the Discrimination between Beta-Thalassemia Trait and Iron Deficiency Anemia Using Different Indexes. International Journal of Biomedicine. 12(3): 375-379.

- Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. (2022). Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 376(9757): 2018–2031.

- Abbas MI, Mohamedahmed KA, Haridy MS. (2024). NRBCs associated leukopenia: alternative formula for correction of leukocytes count: a case study. Journal of Medical Surgical and Allied Sciences. 2(2): 7-11.

- Origa R. (2017). β-Thalassemia. Genet Med. 19(6): 609–619.

- Steinberg MH. (2020). Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 136(21): 2392-2400.

- Musallam KM, Cappellini MD, Taher AT. (2013). Iron overload in β-thalassemia intermedia: an emerging concern. Curr Opin Hematol. 20(3): 187–192.

- Sankaran VG, Orkin SH. (2013). The switch from fetal to adult hemoglobin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 3(1): 011643.

- Ware RE, Aygun B. (2009). Advances in the use of hydroxyurea. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009: 62–69.

- Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV. (1995). Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 332(20): 1317–1322.

- Thornburg CD, Files BA, Luo Z, Miller ST, Kalpatthi R, Iyer R. (2012). Impact of hydroxyurea on clinical events in the BABY HUG trial. Blood. 120(22): 4304–4010.

- Rodgers GP, Dover GJ, Noguchi CT, Schechter AN, Nienhuis AW. (1990). Hematologic responses of patients with sickle cell disease to treatment with hydroxyurea. N Engl J Med. 322(15): 1037–1045.

- Ware RE. (2010). How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 115(26): 5300–5011.

- Olivieri NF, Pakbaz Z, Vichinsky E. (2011). Hb E/β-thalassemia: a common & clinically diverse disorder. Indian J Med Res. 134(4): 522-531.

- Ma Q, Wyszynski DF, Farrell JJ, Kutlar A, Farrer LA, Baldwin CT. (2007). Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia: genetic determinants of response to hydroxyurea. Pharmacogenomics J. 7(6): 386–394.

- Ware RE, Despotovic JM, Mortier NA, Flanagan JM, He J, Smeltzer MP. (2011). Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacogenetics of hydroxyurea treatment for pediatric sickle cell anemia. Blood. 118(18): 4985–4991.

- Lettre G, Sankaran VG, Bezerra MA, Araújo AS, Uda M, Sanna S. (2008). DNA polymorphisms at the BCL11A, HBS1L-MYB, and β-globin loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels and pain crises in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 105(33): 11869–11874.

- Menzel S, Garner C, Gut I, Matsuda F, Yamaguchi M, Heath S. (2007). A QTL influencing F cell production maps to a gene encoding a zinc-finger protein on chromosome 2p15. Nat Genet. 39(10): 1197–1199.

- Stamatoyannopoulos G. (2005). Control of globin gene expression during development and erythroid differentiation. Exp Hematol. 33(3): 259–271.

- Sankaran VG, Menne TF, Xu J, Akie TE, Lettre G, Van Handel B. (2008). Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Science. 322(5909): 1839–1842.

- Pule GD, Mowla S, Novitzky N, Wonkam A. (2016). Hydroxyurea down-regulates BCL11A, KLF-1 and MYB through miRNA-mediated actions to induce γ-globin expression: implications for new therapeutic approaches of sickle cell disease. Clin Transl Med. 5(1): 15.

- Agrawal RK, Patel RK, Shah V, Nainiwal L, Trivedi B. (2014). Hydroxyurea in sickle cell disease: drug review. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 30(2): 91–96.

- Power-Hays A, McElhinney K, Williams T, Mochamah G, Olupot-Olupot P, Paasi G. (2026). Hydroxyurea pharmacokinetics in children with sickle cell anemia across different global populations. Blood Adv. 10(2): 418-427.

- Pandey A, Estepp JH, Ramkrishna D. (2021). Hydroxyurea treatment of sickle cell disease: towards a personalized model-based approach. J Transl Genet Genom. 5: 22-36.

- Dever DP, Bak RO, Reinisch A, Camarena J, Washington G, Nicolas CE. (2016). CRISPR/Cas9 β-globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 539(7629): 384–389.

- Liu N, Hargreaves VV, Zhu Q, Kurland JV, Hong J, Kim W. (2018). Direct promoter repression by BCL11A controls the fetal to adult hemoglobin switch. Cell. 173(2):430–42.e17.

- Molokie R, Lavelle D, Gowhari M, Pacini M, Krauz L, Hassan J. (2017). Oral tetrahydrouridine and decitabine for non-cytotoxic epigenetic gene regulation in sickle cell disease: a randomized phase 1 study. PLoS Med. 14(9): 1002382.

- Esrick EB, Lehmann LE, Biffi A, Achebe M, Brendel C, Ciuculescu MF. (2021). Post-transcriptional genetic silencing of BCL11A to treat sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 384(3): 205–215.

Download Provisional PDF Here

PDF

p (1).png)

.png)

.png)